Artists in Conversation: Lee Deigaard and Sarah Cusimano Miles

Sarah Cusimano Miles, African Elephant (Loxodonta africana) skin specimen, 2010. Pigmented ink print. Courtesy the artist.

Editor's Note

This is the last weekend to catch “Latin for Crab,” a group exhibition curated by artist Lee Deigaard at The Front. The exhibition includes work by Sarah Cusimano Miles and the two artists talk as part of our “Artists in Conversation” series. United by a shared interest in the psychological underpinnings of the image, Deigaard and Cusimano Miles discuss their unique approaches to photographing the natural world, the history of the still life, object memory, and darkness itself.

Raised in Atlanta, Lee Deigaard has lived in New Orleans since 2002 and has been a member of The Front since 2010. She was the 2012 recipient of the Clarence John Laughlin Award for photography and won first prize at the 2012 Southern Open at the Acadiana Center for the Arts in Lafayette.

Sarah Cusimano Miles is a native of Gadsden, Alabama, and is currently Assistant Professor at Jacksonville State University. Having exhibited both nationally and internationally, Cusimano Miles showed her Solomon's House series at Martine Chaisson Gallery in New Orleans earlier this year.

Lee Deigaard: Looking at your work, I'm so blown away by the level of craft and how gorgeous your photographs are. I feel as if I arrived at working in photography via the back door. My graduate degrees are in sculpture and writing, and I did a lot of drawing and painting in school. I really respect deep, discipline-specific skill.

Sarah Cusimano Miles: I can see these different influences in your work and that's exciting. I also worked with sculpture and two-dimensional media, as well as traditional photography, before I went to graduate school. My first degree is in psychology.

I wanted to ask you how you made your nocturnal photographs. Do you have a camera mounted in the forest or do you go and just wait for the animals to arrive?

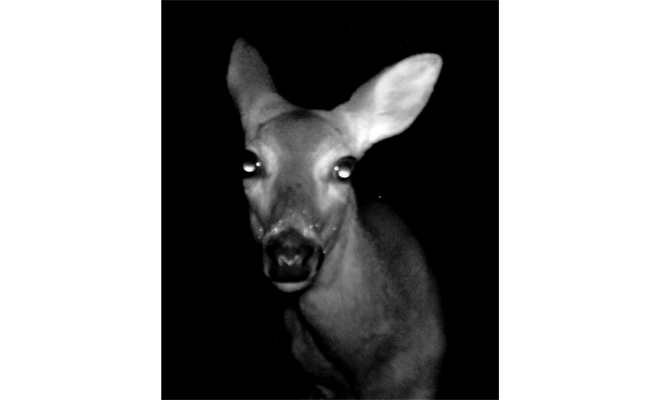

LD: I do a combination of both. I wield the camera handheld, but I also use the motion detector. Both ways, composing is pretty blind and relies on spatial awareness. A sense of collaboration with the animal is central. Handheld, it can feel like a sort of partner dance. I have never really been able to direct my portrait subjects, even the human ones. I’m an instigator, but so are my subjects. My process involves a lot of hindsight. I feel like I discover essential insights mostly after the fact—when I’m doing immense amounts of sorting and sifting, thinking and coaxing.

I work with a fixed population that I feel I know to a degree, if mainly by a shared deep association with the same landscape. I see them in daylight and track their movements by sight and by physical signs. Some of the animals are extroverts and curious and directly engage the camera. They also watch me at a distance. I know they can track me, where I've been, and they know I'm the source of the camera. We interact but in time that has slipped out of key. All the time I spend on the computer feels like a communion with them. It feels intimate.

SCM: Did you grow up on this land as a child and now you're going back to experience the animals as an adult? Or is this work a comment on the hunter and the hunted?

LD: The hunter and the hunted. I wish I could have grown up on that land. I landed there between graduate degrees. I was offered a fellowship and turned it down because I was determined to have a childhood of animals—you know, in my twenties.

I've been interested for a long time in looking at animals as protagonists—how they act as their own agents and on their own behalf. I found the hunter’s camera to be an interesting tool because hunters use them for scouting kills, and this is a region of the country that has lots of hunting going on. I wanted to use the camera for an altogether different aim, an empathetic purpose, in portraits of individuals.

We say “to shoot” a photograph. Animals sense the shutter release, like a trigger reflex. My dogs seem to sense the mere intention to take a photograph. It’s hard to be properly stealthy. I’m constantly dwelling at that edge of availability and readiness. And instinct. I am drawn to seeming mis-shots and thwarted intentions, those really transitory and revealing moments between moments.

When I began I was drawn to just how dark the night can be when you're in the woods. When I work handheld, I'm there in the darkness stumbling around listening for the sounds of breathing and chewing while the horses wait for my blind self to stumble into them. I feel like I am the trespasser. I liked the end result. The discs at the backs of their eyes, their tapeta lucida and the reason for their good night vision, reflect white from the infrared flash I can’t even see. It gives them that gaze as if they're looking through me. It’s not a disinterested gaze exactly, but it puts me in my place a little bit.

SCM: Humbling.

LD: Yes.

Lee Deigaard, Isn't It Pretty to Think So, 2010. Archival pigment print. Courtesy the artist.

SCM: That's one area I found an overlap in our work. When I was doing work at a natural history museum in Alabama, the curator told me this story. At the museum, they have a huge African elephant on display and on the placard it states that the elephant was wounded, which is partly how they came to acquire it. It even shows the spearhead that wounded it. However, the curator said that when they interviewed the people who had gone on this safari, which the museum commissioned, the story was different. The man who shot the animal (a big game hunter) spoke about how he leveled his gun on the shoulder of his guide and shot the elephant, and that the elephant then came sliding towards him.

The story parallels photography in that the truth is fluid. When you go to a natural history museum, you assume that everything you see is real. Likewise, with photography, so many people associate a photograph with the truth; they assume that a photograph depicts facts.

Of course, the notion that these animals are killed to be preserved is a paradoxical rationale, and I started thinking about that as an ethical issue. Photographing the collections not on view and working in the storage area, I started to realize that many of the donated specimens may never end up on display. They represented an excess of the collection. I was simultaneously uncomfortable working with “hunted” or “preserved” specimens, but also very humbled to be able to inspect and handle them. In a way I was hunting the already hunted, preserving the already preserved, and propagating the mythology of the collection with my own invented narratives.

LD: I really related to that body of work because I love bones, feathers, and natural history museums. My sculptural training actually began with an elephant femur.

SCM: I saw the nine-foot elephant that you sculpted.

LD: Yes, I think she's a large chunk of my subconscious or my alter ego that fell out.

Looking at your photograph of the elephant hide, and really all of your work, I was finding all these formal and topical relationships. Bones and objects are like relics that have an almost sacred sense to them. I took a picture once of a pelican at a university’s research facility. The problem with many of the older specimens in drawers there, and other places I’ve been, is that they've been preserved with arsenic so they’re degrading. In spite of the effort to have saved them for posterity, they’re turning into sawdust in drawers. What does that mean for their relic status? Then someone like you comes in, who recognizes the sacred, the life history laden within the object.

SCM: I do see the sacred in it. I'm Catholic and I grew up Catholic, so that's a huge part my visual vocabulary. The work is not expressly religious, but the lexicon of Catholicism infuses itself into the images—the symbolism and the corporeal aspect of spiritual existence.

LD: Reverence? Is that the word?

SCM: Exactly. It's also related to the fact that I grew up next door to my grandmother. She and my grandfather were Sicilian. They're both from New Orleans.

They were married and moved north to Alabama in the 1920s. My grandfather used to love to go back to New Orleans and go to football games and such. My grandmother would get very upset that he was going, so he would always bring her back these gifts—jewelry, hats, gloves, purses. I used to go to her house and play in this room where she and my grandfather slept before he died. After he died, she left most of their belongings in place and slept in a different room. She was a child of the Depression, so she kept everything. It was like a museum. There were all of these objects in the original boxes, delicately packaged and held in drawers and cabinets. I would spend hours going through that room. When I went to the natural history museum, I felt that same kind of reverence, that all of the stored and labeled objects had this intrinsic value.

LD: My grandmother was a little like that too. She was very thrifty, so it wasn't that she bought very many things, but she kept all of them. Discarding things, especially when they’ve survived time, is difficult. A big reason I keep objects is so that I can look at them and immediately access what happened in the past. They are conduits for memory.

A few years back, I was teaching a sculpture class, and I wanted to show my students how to see receding and approaching edges and the processes of abstraction based on perception that bones allow so well, particularly those of large land animals with their flared condyles. I was at the University of Michigan at the time, and they have a natural history museum. Looking at all of the different drawers and cabinets, I got up the nerve to ask if I could borrow an elephant bone. They feel like they weigh forty pounds. The employee handed me one in a garbage bag, and I carried it home on the bus in my lap feeling like I'd robbed a bank. Elephants are said to grieve with the bones of their kin or elephants they knew from migratory routes. They have a mourning process and I felt like that, trying to treasure this bone that's in a plastic bag.

SCM: I love that! I love that you were on a bus with an elephant bone in a plastic bag!

It seems like in our work we both apply a certain anthropomorphic reading to the animals. I saw that especially with your elephant project.

LD: Definitely with the elephant…

SCM: What about with the wild animals in the nocturnal portraits?

LD: With the elephant, I was thinking about how we might gain sympathetic access to animals. It’s the question Thomas Nagel asks: What is it like to be a bat? I thought about our traditions of anthropomorphism—how children grow up with animal characters and then are introduced to eating meat. How much human does the animal need in order to become a sympathetic character to us? So with the elephant, I was thinking about trying to find a way to deal with hybridity, bridging the human and animal worlds in a mingled being. Lactating elephants have two very human-looking breasts between their front legs. I remember when I was in Asia the elephants would recline almost like odalisques.

SCM: Really? I have never seen an elephant do that.

LD: They have ways of doing things that can seem so human. The extreme self-awareness that elephants have with every step they take, I felt like that could be woven into a narrative of how it can feel to be a woman—this self-consciousness that can be acute based on what you think you're supposed to do or how society is trying to coach you. Your posture, your appearance, how much noise you make.

As far as anthropomorphism with the nocturnal wildlife pictures? I think I was trying very hard to do anything but. Often when people work with animals—and there's a lot of work being made with animals—they're symbols, metaphors, or part of a mythology. What interests me is the animal protagonist, her free movements and choices, her curiosity about the camera.

Lee Deigaard, Border Crossing, 2010. Archival pigment print. Courtesy the artist.

SCM: Do you think the anthropomorphic reading can be avoided? Looking at any picture of an animal, it seems like a natural way to empathize with that animal is to assign it your own feelings.

LD: I think of anthropomorphism as a filter of the viewer, a bias in a way, but it doesn’t have to be inherent to the work. Obviously if you draw a pair of pants on a bear and assign him dialogue, anthropomorphism would be innate to that work. And an artist’s unconscious filters, not just the viewer’s, can imbue a piece with suggestive human qualities.

To me, when a raccoon stands on her hind legs and gazes at the lens, she is not aping humanity. It’s within her natural repertoire of movements. My intention is to represent a moment of mutual arrest, raccoon and viewer. If by seeing her standing on two legs, you feel kinship? I am interested in this mutual reciprocity and connection.

Anthropomorphism is definitely a potential empathy lever, and I’m in pursuit of empathy. But I’m also trying to highlight an animal’s autonomy. I’m heartily in favor of humans pondering those who perceive differently, at different volumes, via different organs. I’ve got the introvert’s focus on the one-to-one.

SCM: I see your point. In my work, I guess I use that empathetic read to hopefully elicit a nurturing response, keeping in mind the overbearing way that humans relate to animals and nature in general. I love the Susan Sontag quote about the photographic safari replacing the gun safari. She nails the role reversal of humans and nature in terms of being in danger and requiring protection. She says, "When we are afraid, we shoot. But when we are nostalgic, we take pictures."

LD: That is great! I do worry a lot about impinging on the animals. I aspire to be a tiptoeing trespasser.

Looking at your work, one obvious thing I thought we have in common is the deep blackness in the backgrounds. Your work sent me back to looking at Flemish still lifes and I realized that they also have the black background. In my photographs, I am seeking the deepest black I can get that doesn’t deflect but rather absorbs light. When I was looking at the sculptures and drawings of Lee Bontecou several years back, I saw she had used soot. I remember thinking it was a blackness beyond the blackness you can produce with paint, ink, or charcoal. What is that role of blackness for you?

SCM: There are so many. Even though a photograph abstracts the object, the blackness can abstract it even more, remove it even further from the background, the context. I guess it has a spiritual aspect to me too—that light emerging from the darkness. That's the most interesting place to me—at the cusp of where things come together, that beautiful gradation, that transition and contrast.

LD: Looking at your photographs, it’s not that the animals within them are animate or inanimate; it's that they're suspended. In the way that insight or understanding happens. Where parts cohere, and there's this sort of suspension or illuminated stillness.

SCM: There’s a beauty in the stasis. At the same time, I felt like the preserved specimens I photographed weren't able to complete their lifecycle. You're born, you live, you die, you decay, but they weren't allowed to decay and finish that cycle. That suspension was really interesting to me. I felt a little guilty about it but also fortunate to be able to examine them so closely.

Do you know what a pangolin is?

LD: Yes, I loved your photograph of the pangolin. [a mammal with large plate-like scales].

Sarah Cusimano Miles, Pangolin (Manis gigantean) with garlic, 2010. Pigmented ink print. Courtesy the artist.

SCM: I found that pangolin on a day at the museum when I forgot my tripod, so I was just wandering around marking things to shoot later. It looks like a mythological creature, so surreal, with each scale like a seashell. It was around this time when I started feeling like I was just documenting the specimens, so with the pangolin I decided to bring in objects from outside the museum’s collection to place in the composition with the specimens—a reference to Northern Renaissance and Baroque still lifes and the theme of excess.

Because I was so fascinated with the textures and colors of the animals I was photographing, I needed to capture all of that in the image. To do so, I shot in a grid and then put those images together. I also shot at different focal points for each section, from front to back. I put each section together and masked out everything that wasn’t sharp, then went on to the next section. Some of the images from the Solomon’s House series, which includes the pangolin, are almost 200 composited frames.

LD: Wow!

SCM: After combining the frames and working with the image on the computer, I made a print that was almost seven feet long and lived with it for a while. I would look at it and revise the image then reprint it, and it lived in my mind like that for a while. When I went back to my shooting space at the museum a few weeks later the pangolin was still there. I hadn't put it back on the shelf. I was amazed at how small it was. It was only about two-and-a-half feet long! I thought, “Surely that cannot be right. How can I remember it being so much bigger than that?” That's when I started doing some research in visual perception and how we form memories from our visual information. I found studies about how we actually remember the last time we remembered something, not the original instance. So every time you remember something, you make a new memory, which made total sense to me. My dad is an attorney and he's been examining that for years. Witnesses can be unreliable because they remember the last thing that they thought about. That's how memories can shift and change. When you have an object that doesn't change most of the time or a photograph, which stays the same, it's such a huge mechanism for shaping memories.

LD: Do you think photographs are about witnessing? To me, in my work, to witness is so important. It’s an almost moral act because it means to not look away. I think about you and your close examination, the labor of capture—to preserve, to transform.

SCM: I think my photographs are about witnessing, but also about realizing the ambiguity in truth. The many levels a photograph can hold within it whether it be truth, fiction, or somewhere in between.

Editor's Note

“Latin for Crab,” curated by Lee Deigaard with work by Sarah Cusimano Miles, on view until August 4 at The Front (4100 St. Claude Avenue) in New Orleans.